|

Matron Gertrude Riding OBE

Gertrude Riding was born in Gateacre in 1891, but lived for the rest of her life between the nurses homes of Mill Road and Alder Hey, and the family home in Halewood. She became Matron of Mill Road Hospital in Liverpool in 1927, and her brave actions and courage during the May Blitz of 1941 saw her awarded the OBE.

Her father was William Riding, who had moved to Gateacre from Church Lane, off Southport Road, Lydiate, near the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, where his father also named William worked as a bricklayer.

Matron Gertrude Riding OBE

Gertrude Riding was born in Gateacre in 1891, but lived for the rest of her life between the nurses homes of Mill Road and Alder Hey, and the family home in Halewood. She became Matron of Mill Road Hospital in Liverpool in 1927, and her brave actions and courage during the May Blitz of 1941 saw her awarded the OBE.

Her father was William Riding, who had moved to Gateacre from Church Lane, off Southport Road, Lydiate, near the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, where his father also named William worked as a bricklayer.

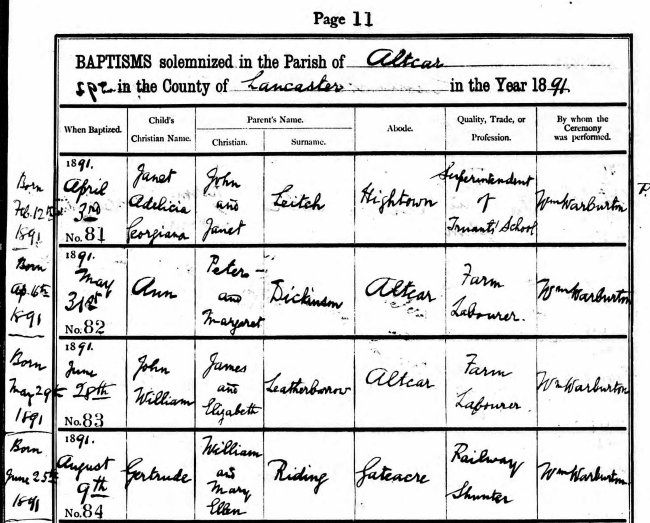

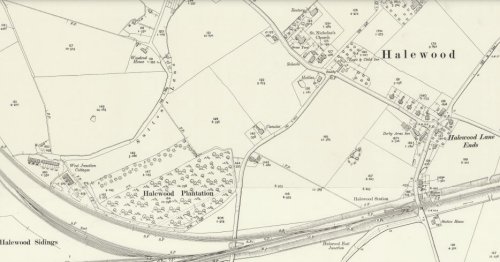

William had secured a job as a shunter on the recently opened railway (in the Halewood Triangle sidings) and moved to Gateacre near to his workplace. On 3 November 1889, he married Mary Ellen Rotherham of Alcar in St Nicholas Church, Halewood, and rented one of the small terraced cottages on Halewood Road, near the Gateacre cross roads. On 25 June 1891 their first child Gertrude was born, and they travelled to Mary’s home in Altar to have her baptised in the family church on 9 August 1891. (Altcar village was just a few hundred yards on from Church Lane, Lydiate, so both families could easily attend).

|

|

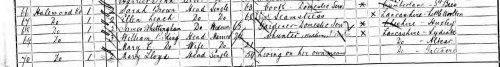

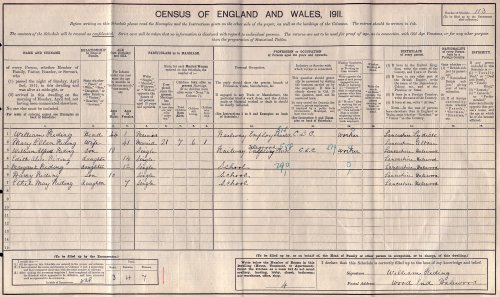

1891 Census - William and Mary Riding in Halewood Road, Gateacre

Birthplace of Gertrude Riding

|

|

|

Gertrude's baptism in Altcar Parish

|

The following year, the young family moved into one of the ‘Railway Cottages’, built for the workers on the Halewood Triangle sidings. By 1901, three brothers and two sisters had been added to the family, and they had moved across the village to Bailey's Lane, possible to be closer to Halewood Station which was located there at the time.

|

|

1901 Census - Riding family in Bailey's Lane, Halewood

|

<

The original Halewood Station, Bailey's Lane

The original Halewood Station, Bailey's Lane

As a teenager, Gertrude was intent on a career in nursing, and in 1908 aged seventeen, she began work as a trainee in Liverpool Radium Institute.

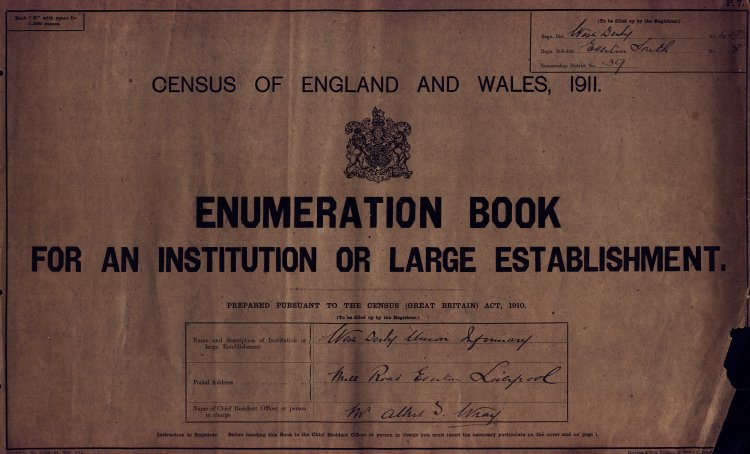

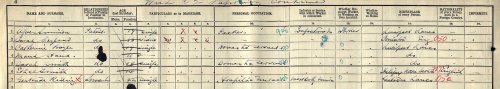

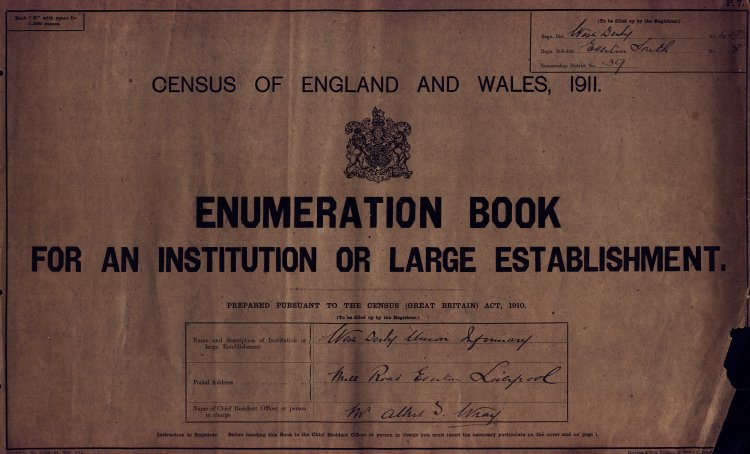

Meanwhile, the first meeting of the National Council of Trained Nurses of Great Britain and Ireland was held in London in 1908 and during the first decade of the twentieth century, hospitals were increasingly establishing their own training schools for nurses. In exchange for lectures and clinical instruction, students provided the hospital with two or three years of 'skilled free nursing care', (which explains why they were listed as ‘servants’ rather than trainee nurses in the 1911 census). Gertrude found such a position as a probationer in the West Derby Union Infirmary in Mill Road, formerly the hospital for the West Derby Workhouse.

|

|

Mill Road Census 1911 - Gertrude listed as a 'servant' (as all trainee nurses were)

|

|

|

1911 Census - Riding family now in Woodend

|

|

|

1905 Halewood Sidings and Railway Cottages (West Junction Cottages on map)

Riding family now in Woodend, Halewood (centre left on map)

|

By 1913 she had qualified and received her nursing certification. Three years later she was a founder member of the Royal College of Nursing. It is likely that she was then serving abroad in the latter stages of the First World War, as later newspapers of the 1940s commenting on her career by then, stated she was ‘Mentioned in Despatches for service to the wounded’. However, any trace of a war record has yet to be found (this is due to the inconsistent records kept, rather than any doubt cast on her service).

Mill Road Hospital pictured in 1925

Nurse Riding continued her service at Mill Road, becoming Assistant Matron in 1921, and unusually served in every position, before being appointed Matron in 1927 at the age of thirty-six. During the 1930s, she was also recognised for service to the community with the George V Jubilee Medal of 1935, and the Coronation Medal of 1937 (George VI).

|

|

|

King George V Silver Jubilee Medal 1935

|

King George VI Coronation Medal 1937

|

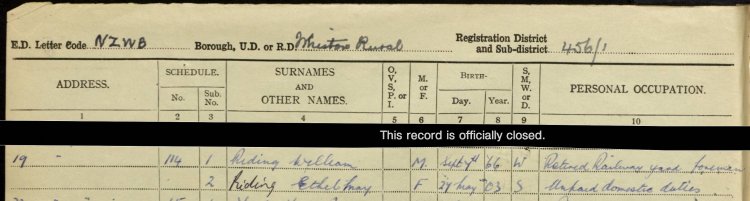

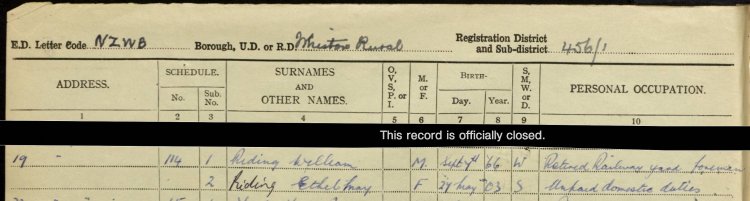

Her family meanwhile, continued to live near the sidings at Woodend, while during her working hours Gertrude had rooms in the Nurses Home at 118a Mill Road. By 1939, her widowed 70 year old father William was retired (having reached the position of yard foreman in the Railway sidings), and living with Gertrude’s younger sister Ethel May in a cottage at 19 Bailey’s Lane (Ethel was also living in Arthur Street, Walton, through the 1920/30s and is thought to have been working as a nurse, living in the Nurse's Home for Walton Hospital).

1939 census - 19 Bailey's Lane, Halewood

But now war was looming, the events of which would be life-changing for Gertrude.

The Blitz on Mill Road Hospital

Saturday 3 May/4 Sunday 4 May

The night of 3 May 1941 will live long in the memories of those who lived through it, and will always be remembered as the worst night ever experienced on Merseyside for the terrifying all-out assault, and the death and destruction inflicted upon an already war-weary population. The raids lasted for six and a half hours, from half past ten in the evening of the 3rd to five o’clock the following morning. Three hundred enemy aircraft invaded the skies and dropped an estimated 50,000 incendiaries, lighting up a clear path for the 360 tons of high explosives to follow. Few areas were untouched, with over 300 reported incidents. The damage and loss of life were the heaviest of the war…

…Across the city, several hospitals were hit, including the Royal Southern near the south docks, but by far the worst of the damage and loss of life was at Mill Road Hospital near Everton. At the beginning of the war, the Emergency Hospital Scheme was set up as a part of the Emergency Medical Services. Around fifty hospitals were included within the Merseyside group, under the command of K.W. Monsarrat TD MB FRCS Ed., and during the winter of 1939–40 a number of these were either suspended or withdrawn from the scheme, owing to their unsuitability for the treatment of casualties. Due to its close proximity to the docks, the Royal Southern was transferred to Fazakerley, the David Lewis Northern to Childwall, and Bootle Hospital to the Bootle Isolation Hospital.

Mill Road, meanwhile, made preparations to act as a wartime casualty hospital, while the maternity wards continued to function as normally as possible. The hospital had already been hit, in September 1940, and in November the Nurses’ Home adjacent to the hospital was destroyed.

At around 11pm on the night of 3 May, Dr Gray, the deputy medical superintendent, surgeon Mr Digby Roberts and anaesthetist Claude Watson were in the operating theatre preparing for abdominal surgery on a Greek seaman. Assisting were Nurses Froom, Jeffries and George, plus Glenys Pierce, a Junior Theatre Sister, who was supposed to be off duty, having come in specially for the operation. As they were about to start, the dreaded air-raid warning sounded. The team agreed to continue; they were in the basement anyway.

Meanwhile, over in the maternity unit, those who could walk were sent down to the basement shelter, accompanied by several staff. This left the newly appointed Sister Reid and two pupil midwives to care for the remaining patients. Their beds were pulled well away from the windows and mothers were given their babies to hold. One of the pupil midwives that night was Nurse M. Travis:

We did our best to reassure the patients, but after a very severe explosion nearby, which shook the whole building, one of the antenatal patients became hysterical and demanded to go to the shelter. We tried to persuade her to stay, as she had had complications, but to no avail. The other pupil midwife took her down to the shelter. It was not a busy night, only one patient being in early labour and she was put in the ward with the other patients. Sister and I took a ward each. We took the premature babies into the ward to feed so that we didn’t leave the mothers.

One of the patients, Mrs Spencer, felt fit enough to travel downstairs. Clutching her baby daughter to her chest, she made her way to the basement. The makeshift shelter was a small room at the end of the basement corridor, shored up with timber pit props, with a single small light hanging from the ceiling. She sat down on a mat below a window, and placed her gas mask beside her. On the other side of the room, in separate cots, were three or four children aged no more than twelve months. They were standing up and crying, while a young nurse tried her best to soothe them. The noise of the guns and the bombs grew louder. Mrs Spencer remembered:

My baby started to cry, so I turned myself to the wall to feed her. Then this big ‘WHOOF’ came. I thought my ears had burst as the dust and glass came showering down. I think I avoided getting cut as I was facing the wall. It was obvious we had been hit, the room was lit up by the fire above. I couldn’t see anything of the young nurse or the children – all had gone quiet. I couldn’t feel anything on top of my legs so I got up – I left the gas mask – not much point really, I walked through into the wide corridor and stood opposite the stairs alongside the lift which I had come down in. The fires were raging above and lit up everywhere. The floor was littered with glass. Where I was standing, there was a room behind me, so I thought I would see if there was a way out. I opened the door and it was icy cold. I stopped to focus my eyes and I realised I was staring at bodies on tables covered with sheets. I went out quickly. My Grandmother had died in this hospital only a few weeks earlier and I shivered as I felt her presence. I went back to where I had been standing before. Other people were there but there was no screaming or shouting, just bewilderment. The firemen in the yard had been playing water on the lift and had stopped the fire, but the water was now cascading down the shaft and stairs.

Then some youths, probably only about fourteen, came running down the stairs and one came to me and said, ‘Come on Missus, you get on the side of the stairs nearest the lift and I’ll take the side with the water.’ When we got to the top of the stairs and the front door, I could see about four fire engines in the yard. The boy told me to go through the yard and turn left down Mill Road to the clinic on the corner and we would get help. I knew where he meant as I was born and brought up in Hughes Street [it backed onto the clinic]. The boy went back down to help the others to get out.

Back in the maternity ward, Nurse Travis was making her report to Sister Reid on the new admission who was still in labour.

I returned quickly, and as I approached the ward entrance there was a terrific explosion, the whole building shook and debris was falling all around. The whole place was in darkness. When the vibration ceased, to my horror the ward I had just left with Sister in charge was no more. Sister Reid and all the patients on that ward had been killed.

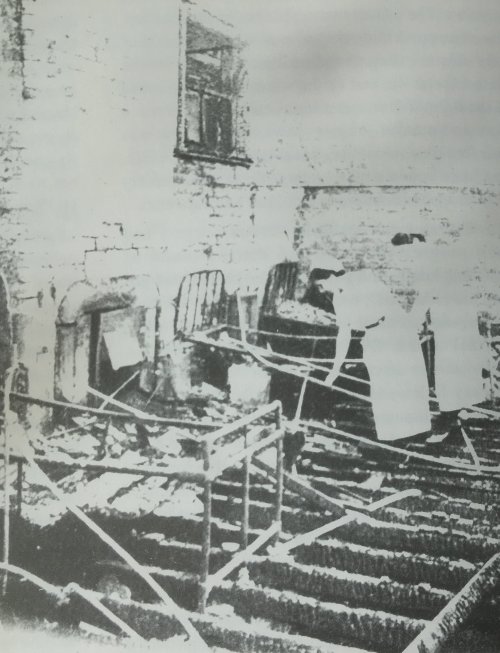

In the basement operating theatre, the Greek seaman had been anaesthetised and the surgeon had made the initial incision. Nurse Winifred Froom recalled:

No sooner had he done so then there was a ‘SWISH’ and a ‘SWOOSH’ and all hell broke loose. Total darkness descended on us, the sound of falling masonry followed, coupled with the cascading of water from innumerable broken pipes. I was flung face downwards and I remember waiting for something to fall and crush me too. But it didn’t, and realising this I scrambled to my feet and climbed through a shattered window immediately behind me, an athletic feat I could never have achieved under ordinary circumstances!

Glenys Pierce remembered:

The first thing I remember hearing was Mr Roberts saying that he had lost his glasses. There was a slab of stone across my body, and from above everything was falling in. The patient was still on the table, but it was tilted, like a see-saw. There was a nurse who had fallen through the hole in the basement. She was hysterical, clutching her head and crying that she could not see. I could see a way out through a blown-out window and I got her out through there. I told the rescue party how to get into the basement, then took the nurse to outpatients.

Nurse George also escaped through the window and returned with rescuers. Anaesthetist Claude Watson received a blow to the face, later losing an eye. The Greek seaman, still anaesthetised by the injured Watson, was recovered from the wreckage, and later transferred to Walton Hospital, where surgeons completed the operation. ‘He was in the same hospital that I had been sent to after the bombing and was now making a relatively uneventful recovery in his new surroundings,’ said Winifred Froom. ‘Of course, I went to see him, but the language barrier was too wide; he knew no English and I knew no Greek, and I failed to get him to understand how lucky he was to be alive!’

Those in the operating theatre that night working on the seaman were not so lucky. Deputy medical superintendent Dr William Gray perished, as did two medical students attending the operation, Morris Lyons and Harold Young. The body of Nurse Lydia Jeffries remained buried below the rubble for eleven days. As one of the rescue workers gently lifted her out, her wristwatch caught his eye. It had stopped at 11.25pm.

Earlier that Saturday evening, Nell Hawkins, an auxiliary nurse of the Civil Nursing Reserve, was one of those helping to pull the beds away from the windows in the maternity ward when the air raid sounded. Quickly finishing the task, she dashed downstairs to report for ambulance duty. A short time after the bombing commenced, the phone rang in the ambulance room. According to the rota, the first nurse due to go out with a driver was Nurse Whitley. As she was still suffering from a traumatic experience she’d had during the previous night’s bombing, while rescuing a severely injured 16-year-old girl, Nell Hawkins insisted on going in her place. After much persuasion, backed up by one of the drivers, Nurse Whitley returned to the ambulance room, where around twenty drivers and attendants anxiously awaited their turn. Just as Nurse Hawkins and her driver got in the cab, the land mine hit the hospital.

My partner and I threw our arms around each other, held our breath and didn’t utter a single word. As the hospital collapsed and the debris continued to fall, it seemed that the whole of Liverpool had crumbled around us. Many of the ambulances nearby were completely destroyed. Unbelievably, ours remained standing, until one of the flying bricks hit the roof and shattered the windscreen. We slid sideways as the vehicle did the same. The driver was unhurt and I escaped with a cut finger. As we recovered our senses, an incendiary bomb fell on the ambulance room. It was dreadful, the room immediately burst into flames and fourteen of the twenty-two drivers, along with Nurse Whitley, perished in that terrible fire. The debris was still falling around us and the noise was terrifying.

Later, Nell learned that the maternity ward she had left moments earlier had also been destroyed. She had escaped death three times within the hour. Nell Hawkins’s feelings were mixed. While thankful that she had been spared, she found it difficult to come to terms with the fact that Nurse Whitley might have lived if she had not taken her place on the rota. Yet Nell was not given time to dwell on the dreadful tragedy:

It was the longest night I’ve ever experienced – a night of stepping over bodies, some breathing, others strangely quiet, frantically searching for bandages, sheets, pillows, blankets, water – and not forgetting friends and colleagues. Once most of the patients had been transferred to other hospitals, things began to quieten down. Someone told me I could go home. I couldn’t find the cloakroom, it was like a wilderness, so I started to walk home, minus my money and belongings. Well past Sheil Road and two thirds of the way home, a passing motorist offered me a lift. In I climbed, tired and dulled, covered in blood and grime. When I got home a horrified neighbour sympathised before mentioning that the Automatic (Plesseys) had been blitzed too. I collapsed into a chair. My husband Hal was on duty there with the Home Guard and I couldn’t relax until I heard him come through the door. We fell into each other’s arms as I hugged my husband of one year. Hal had had a quiet night – the Automatic hadn’t been bombed after all.

In the clinic, Mrs Spencer, having been rescued from the basement shelter, sat down at the side of the room, dazed and bewildered. Injured people were everywhere amid the dreadful conditions.

The room was lit with one emergency light hanging from the ceiling. A Doctor came round, his arms were broken and he was pressing his palms together to keep them up. He must have been in terrible pain. There was a nurse with him and he was asking us what our injuries were, before giving the nurse instructions of what to do. In the meantime, the bombs were dropping and the glass partitions were shaking – I was expecting them to shatter at any moment. By this time, there were about five or six women sitting beside me on the bench, when a hospital porter with a nurse came into the room with a clothes basket with new born babies in it. The ladies jumped up and grabbed one each. I don’t know how they knew which was theirs, as the light was too dim to read the names on the wrist tags. A few minutes later, an ambulance driver came in and asked if anyone was willing to take a chance he would drive them to Broadgreen Hospital. He said he would drive without lights but not to worry as he knew the way blindfolded.

Needing little encouragement, Mrs Spencer followed him outside to claim the last seat in the ambulance. Opposite, on the bottom stretcher, lay the doctor with the broken arms. Another victim, still moaning in pain, lay on the top stretcher. Not a word was spoken throughout the journey. After safely making the journey without further incident, the ambulance returned to Mill Road to ferry more casualties.

At Mill Road, the rescue operation had continued throughout the night. Civil Defence, medical staff, nurses, off-duty staff who had dashed to the scene and local people, all struggled to do what they could in impossible circumstances, without water, light or adequate medical supplies, and with fires raging around them. Even the ambulance depot was destroyed, hampering the swift transfer of victims. The rescue work continued for several days afterwards. Winifred Froom recalled,

There were many unsung heroes and heroines that night, nurses with caps and collars awry, carrying stretchers to and fro, a little team of doctors who went from patient to patient, administering pain-killing drugs to those for whom it was not too late. Only when we could do no more, did we greet the dawn at the hospital gates, where a WVS van waited, issuing tea and corned beef sandwiches to nurses and doctors alike. I remember the sandwiches even now.

Gradually, news filtered through of the cost of that night’s work. We had lost doctors, nurses and patients in the holocaust. Those of us who had escaped unhurt were split up and allotted to suburban hospitals to help deal with the influx of patients they had received, including some of our own injured staff. We knew, however, how lucky we were to be alive.

Leonard Findlay, the medical superintendent, who had directed his medical staff throughout the rescue, despite being wounded, received the George Medal for bravery. The citation declared:

Leonard Findlay, the medical superintendent, who had directed his medical staff throughout the rescue, despite being wounded, received the George Medal for bravery. The citation declared:

Dr Findlay displayed outstanding courage and devotion to duty when the Mill Road Infirmary was badly damaged during an air raid. Although badly shaken and severely burned he immediately organised rescue work and personally led parties of volunteers to release persons trapped under the wreckage. He worked without ceasing throughout the night and following day, and refused to have his own wounds treated until he had accounted for all his patients and staff. Under his cool and courageous direction many lives were saved and all the patients evacuated to other hospitals.

London Gazette, 5 September 1941

Dr Findlay was part of the medical rescue team that had attended the Durning Road bombing back in November, when he had crawled through the wreckage giving painkilling injections to those trapped so they knew less of what was happening. In 1942 he was appointed medical superintendent of Broadgreen Hospital, where he remained until his retirement.

Matron Miss Gertrude Riding worked tirelessly to release an auxiliary nurse and the chaplain, who had been pinned down by debris, despite receiving an injury to her eye, which she later lost. Miss Riding received an OBE:

Matron Miss Gertrude Riding worked tirelessly to release an auxiliary nurse and the chaplain, who had been pinned down by debris, despite receiving an injury to her eye, which she later lost. Miss Riding received an OBE:

Miss Riding has been most active in the reception and treatment of air raid casualties and her loyalty and enthusiasm have greatly encouraged the Nursing Staff and contributed to the smooth running of the Hospital. When the Nurses’ Home was partially demolished by a high-explosive bomb, she did not hesitate, despite the danger, to make an immediate search of the premises.

Later, when the Hospital was badly damaged by enemy action, Miss Riding was seriously injured. Nevertheless, despite the fact that she was unable to see owing to an eye injury, Miss Riding was instrumental in releasing a nurse who was trapped and she endeavoured, before she finally collapsed, to help another injured member of the staff. Miss Riding’s conduct has been an example of devotion to duty and self-sacrifice in the service of the Hospital.

London Gazette, 29 August 1941

These were fitting tributes from the nation for the gallantry shown, not just by Dr Findlay and Matron Riding, but by everyone involved in the battle so heroically fought that night.

A variety of casualty figures have been published over the years, but official details were given as follows:

All the surviving patients, who numbered about 400, had to be transferred to other hospitals. 83 persons in the hospital were killed and 27 injured, including 17 members of staff killed and 22 injured.

The Deputy Medical Superintendent Dr Gray, the Deputy Matron, Miss L. Handley, two resident medical officers, eleven nurses, a clerk and a porter were killed. The Medical Superintendent, Dr L. Findlay, the Matron, Miss G. Riding, fifteen nurses, the chaplain and four porters were wounded. In addition, 14 drivers and attendants in the Emergency Ambulance Depot were killed and three injured. This mine, therefore, was responsible for the deaths of 97 persons.

C.L. Dunn, Ed. ‘The Emergency Medical Services Vol II’, from the series ‘A History of the Second World War – United Kingdom Medical Series’ (1953) p.329

When the damage to the building was assessed, it was discovered that three ward blocks had been totally destroyed, and all the in-patient accommodation rendered uninhabitable. The out-patients’ department, constructed only two years earlier, escaped damage.

On Sunday 4 May, Nurse Winifred Froom looked out on the new day. Many years later she remembered:

Not only was the weather glorious, but there was a spirit abroad we’d never encountered before. A camaraderie, a unity, a sharing hitherto unknown to us. Transport to and fro was inevitably disrupted, but we never had to beg for a lift; on the backs of lorries, in small vans and large, we were welcomed and catered for. If only that wonderful spirit could have been maintained until now. If only we could have communicated some of our overwhelming determination to put an end to the slaughter. If this effort to recall some of the events, suffering, sacrifices and dramas that we experienced can contribute towards making sure war is outlawed for ever and ever, it will be worthwhile.

Extracted from;

Mike Royden, Merseyside at War 1939-45, (Pen & Sword 2018)

Mike Royden, ‘The May Blitz’, in Mill Road – The People’s Hospital, (1993) pp.27–35

|

|

|

|

Mill Road – The People’s Hospital

(Download a full pdf copy here)

|

Merseyside at War 1939-45

(Order online here)

|

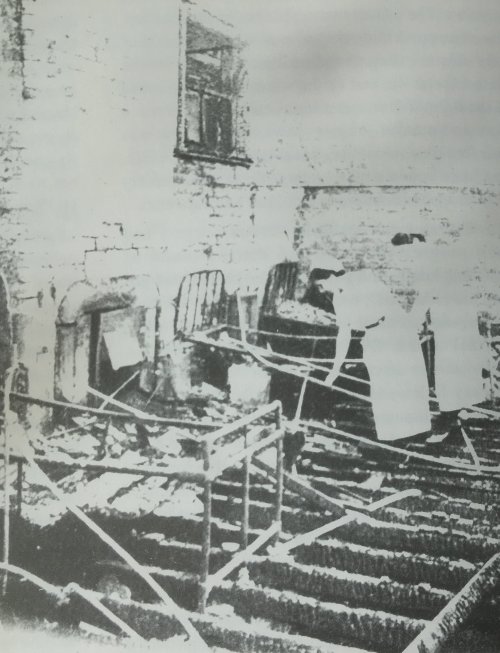

Mill Road Hospital - Blitz damage May 1941

Mill Road Hospital - Blitz damage May 1941

Mill Road Hospital - Blitz damage May 1941

..................................................

Matron Gertrude Riding OBE

|

|

|

|

O.B.E nomination (part one)

|

O.B.E nomination (part one)

|

O.B.E London Gazette Citation

|

Gertrude had been transferred to Alder Hey – as a patient - to receive treatment for her wounds and undergo an operation on her damaged eye, which could not be saved. Meawhile, in her absence she was appointed the new Matron of Alder Hey Hospital in June 1941, despite still being in a convalescent home in Tarporley undergoing her recovery.

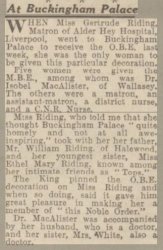

After six weeks, Matron Riding was discharged, and she took up her new appointment on her return, although in October she had an important appointment to keep, and would be accompanied by her 76 year old father and her younger sister;

|

|

|

|

Gifts for Matron

Liverpool Daily Post,

29 October 1941

|

Decorated by the King

Liverpool Echo,

29 October 1941

|

At the Palace

Liverpool Evening Express,

31 October 1941

|

Retirement

Matron Riding continued her work at Alder Hey until her retirement, after forty years of nursing, on 30 June 1948.

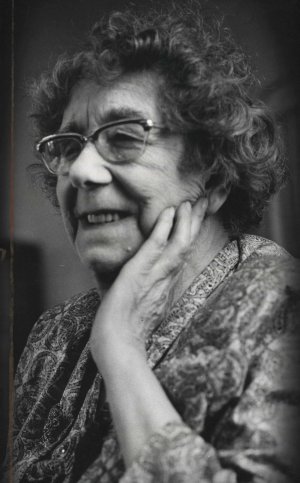

(Right: Matron Gertrude Riding receiving her gifts on the occasion of her retirement)

At the party given in her honour, she was presented with an inscribed silver tablet and £100 (to purchase an antique dressing table!) by Alderman Ernest Cookson. Chairman of the Hospital Committee. Tributes flowed, including one from Dr W.M. Frazer, Medical Officer of Health for Liverpool, who described Miss Riding as ;one of the great matrons who had trained in Liverpool; and, admiring her humanity, said “Not every matron has such a human touch with the nurses under her charge.”

(Liverpool Daily Post 22 June 1948)

At the party given in her honour, she was presented with an inscribed silver tablet and £100 (to purchase an antique dressing table!) by Alderman Ernest Cookson. Chairman of the Hospital Committee. Tributes flowed, including one from Dr W.M. Frazer, Medical Officer of Health for Liverpool, who described Miss Riding as ;one of the great matrons who had trained in Liverpool; and, admiring her humanity, said “Not every matron has such a human touch with the nurses under her charge.”

(Liverpool Daily Post 22 June 1948)

Such humanity was clearly apparent to a young probationer formerly under her care;

‘When the strangeness of the new life had gone, I realised that Mill Road Infirmary was a very happy place. This, I’m sure, was because the Matron, Miss Riding, was such an impressive character. She was a person we all respected and trusted. She treated us fairly, without exception, and would listen to us if we had any complaint, before giving her own opinion. She considered the welfare and happiness of her staff to be all important, and she would help in any way she could, should any of us be in trouble. Her advice was always sound, and we had no fear of going to see her at any time. The hospital was a happy place because Matron set such a splendid example. Consequently, all that she represented work down through the staff to the most junior level’

Extracted from Nurse Margaret McFadden’s (nee Fryer) printed notes of her memories of Mill Road Hospital 1937-40 (Now in Mill Road Archives).

Miss Riding retired to her home in 19 Bailey's Lane, Halewood, although she continued to be active in the affairs of Alder Hey after being appointed to the management committee.

Her sister Ethel May had died in June 1943 aged just forty, and her father William in April 1952 aged 85. Both were laid to rest in the family plot in village churchyard at St Nicholas.

Her sister Ethel May had died in June 1943 aged just forty, and her father William in April 1952 aged 85. Both were laid to rest in the family plot in village churchyard at St Nicholas.

Gertrude Riding OBE died on 13 January 1975. It may have been three decades since her retirement, but the news still made the front page of the Liverpool Echo. Gertrude was laid to rest in St Nicholas with her family.

A short time before she passed away, she was interviewed at the age of eighty by the Echo about her memories of that fateful day in May 1941. Here below are her own words and thoughts about those events which had occured three decades earlier to the day.

|

|

Memories of the May Blitz thirty years on.

Liverpool Echo, 13 May 1971

|

Return to Halewood Inhabitants Page

www.roydenhistory.co.uk

Visit the Royden History Index Page listing web sites designed and maintained by Mike Royden

No pages may be reproduced without permission

copyright Mike Royden

All rights reserved

|

At the party given in her honour, she was presented with an inscribed silver tablet and £100 (to purchase an antique dressing table!) by Alderman Ernest Cookson. Chairman of the Hospital Committee. Tributes flowed, including one from Dr W.M. Frazer, Medical Officer of Health for Liverpool, who described Miss Riding as ;one of the great matrons who had trained in Liverpool; and, admiring her humanity, said “Not every matron has such a human touch with the nurses under her charge.”

(Liverpool Daily Post 22 June 1948)

At the party given in her honour, she was presented with an inscribed silver tablet and £100 (to purchase an antique dressing table!) by Alderman Ernest Cookson. Chairman of the Hospital Committee. Tributes flowed, including one from Dr W.M. Frazer, Medical Officer of Health for Liverpool, who described Miss Riding as ;one of the great matrons who had trained in Liverpool; and, admiring her humanity, said “Not every matron has such a human touch with the nurses under her charge.”

(Liverpool Daily Post 22 June 1948)