|

|

Halewood Local History Pages The Buildings of Halewood

Halewood Parish Workhouse

Halewood Parish Workhouse was a cottage in Wood Lane (later 'Workhouse Lane' and now Hollies Road) near the present site of the Hollies Hall village community centre. It was part of the Old Poor Law system, in use from the 18th century until the introduction of the New Poor Law in the 1830s.

The seeds of the Poor Law are in the Elizabethan desire to remove vagrants and beggars from the streets and to introduce an legislative framework to deal with the growing problem of the poor. In 1601, during the reign of Elizabeth I, an Act of Relief of the Poor was passed which was to be the basis of Poor Law administration for the next two centuries. It divided the poor receiving relief into three categories –

(ii) the rogues, vagabonds, and beggars, who were to be whipped or otherwise punished for their unwillingness to work. (iii) the 'impotent' poor (the old, the sick and the handicapped), who were to be relieved in almshouses. By the provisions of the Act, each parish was made responsible for its poor. It would appoint its own Overseers of the Poor (usually the church wardens and a couple of large landowners) who would collect the poor rate. The money would then be spent in four main ways:

(ii) 'for setting to work all such persons married or unmarried, having no means to maintain them, and who use no ordinary or daily trade of life to get their living by' (that is, the able-bodied pauper). (iii) 'for providing a convenient stock of flax, hemp, wood, thread, iron, and other ware, and stuff to set the poor on work'. (iv) 'for the necessary relief of the lame, impotent, old, blind and such other among them being poor and not able to work'.(1) The Act also made it legal 'to erect, build and set up convenient houses or dwellings for the said impotent poor and also place inmates or more families than one in one cottage or house', which appears to be the initial authority for the erection of buildings later to become known as workhouses. A number of parishes took up this option realising there was a considerable saving to be made compared with supporting paupers within their own homes or as vagrants. Further Acts were passed over the next two centuries to extend the administration or to prevent abuse of the system. However, there was a disparity between the size of parishes in the north of the country compared with those in the south, which was ignored in the initial implementation of the 1601 Act. Childwall, for example, comprised nine townships, including Halewood, each of which were of similar size to parishes in the south.(2) This anomaly was largely addressed by the settlement Act of 1662, which made each township responsible for its own poor, especially if they had resettled elsewhere.(3) Parishes were permitted to send paupers back to their own parish to receive relief if they became a burden. (This stayed in place until 1945).

Left: Settlement certificate of 6 February 1726

A second key development in poor law legislation was Knatchbull's General Workhouse Act of 1723, which enabled single parishes to erect a workhouse if they wished, so that they could enforce labour on the able-bodied poor in return for relief. (4) This 'workhouse test' would enable parishes to refuse relief to those paupers who would not enter them. Nationally, the building of workhouses increased considerably under this Act, and by the end of the century their number had increased to almost 2,000, most holding between 20 to 50 inmates. The poor rate was greatly reduced, especially now that the poor were suffering the workhouse test and there was strict application of the law; - for example, there would be no relief for the outdoor poor, unless a written order was given by the mayor or a Justice of the Peace. In the surrounding parishes and townships, if a workhouse existed it was usually a small cottage rented for the purpose. Records in many cases appear to no longer exist and although certain references have been found, the existence of the building itself is often still dubious. In West Derby however, we can be more certain; the parish workhouse known as the Old Poor House, is known to have stood since 1731 on the northern side of Low Hill, near to the present site of the Coach and Horses and was in use until the late 1830's.(5) Other rural workhouses were known at Huyton (1732), Prescot (1732-50), Speke (1742-76), and Woolton (1834-37). Others may have existed, probably for a short period, at Allerton (1776), Childwall (1776), Ditton (1776), Hale (1776), Cronton (1770-89), and Wavertree (1776) (where a local parishioner was paid to marry a woman and take her off the poor relief!).(6)

One of those rural workhouses was in Halewood.  Halewood Tithe Map (extract) 1840

Halewood Tithe Map (extract) 1840Halewood is a typical example where local townships largely dealt with their own poor. Records show that overseers spent money on outdoor relief, mainly to the sick and unemployed on a short term basis, and more permanently on orphans and the elderly. Paupers were boarded out for a year at a time in the community, while others received money for board, clothes, shoes, coal and services of a doctor. A copy of the new Act was purchased for 7d in 1722, following which a cottage was rented from Earl of Derby at 6d per year (although this was in the hands of John Ireland Blackburne of Hale by the end of the Old Poor Law). Most of the overseer's time and expense was spent dealing with the problem of policing the settlement issue. Inevitably, much of what is written about this period reveals the grim face of the poor law administration. Attitudes in the local townships were probably more informal and more sympathetic than those of the hard pressed overseers of the Liverpool Vestry constantly battling against the huge demand placed upon them. As Janet Hollinshead observed in her study of 18th century Halewood, ‘When the Overseers of the Poor could provide Hannah Hitchmough, an elderly lady, with not only her board and clothes, but also with tobacco to smoke, and when they also gathered flowers for a pauper, Samuel Stevenson’s funeral, it does suggest that they knew the people concerned and that they cared’.(7)

Earl of Derby estate map (extract) 1783

Earl of Derby estate map (extract) 1783The workhouse building shown in the centre

Halewood enclosure map (extract) 1805

Halewood enclosure map (extract) 1805The workhouse building shown in the centre (just above no.38) While studying the birthrate between 1700 and 1725, Janet Hollinshead also noted,

'At this same time there is evidence of nine illegitimate births, including one of the sets of twins. This represents an illegitimacy rate of one in fifty-seven births, 1-8 per cent, an incredibly low rate. Some texts refer to a rate of 5-0 per cent as being 'low', yet a comparable figure with that in Halewood has been found also for a rural area of Shropshire in the early eighteenth century. Baptisms in general appear to be relatively well recorded with the presence of very few other children becoming apparent from wills and other documentation, and amongst the township records there is clearly an anxiety to record the parentage of illegitimate children presumably to ensure avoidance of future financial liabilities. In eight of the nine cases of illegitimacy the father's name is known and in seven instances they came from Halewood; two of the fathers were married already. One imagines Robert Ives caused something of a local scandal when he fathered two illegitimate children to different women in 1719, and then left a considerable financial burden to the township when he died in 1720. Most mothers of illegitimate children remained in Halewood for at least several years after the birth of their children. If they left their chance of maintenance from the father and/or the township was much reduced. (8)In the eyes of the Overseers, this financial burden falling on the township was to be avoided, consequently when a woman fell pregnant with a child likely to be born illegitimate, she was legally obliged to notify her parish of settlement at least forty days prior to the expected birth, and submit to a Bastardy Examination. In practice, such examinations were frequently held after the birth, and were held before two Justices of the Peace. The examination was directed at forcing the mother to swear to the name of the father of the child. This in turn allowed the parish to seek an indemnity from the named father against any charges it might incur in supporting the child and mother. Fathers who could be identified in this way were obliged to enter into Bastardy Bonds to ensure that they paid regular support to the mother and child. If they failed to pay this support, they were legally obliged to pay the parish a substantial sum in compensation, often to the amount of £60 to £80. The amounts involved were such that few men could indemnify the parish from their own resources, and friends and relatives, as sureties, were normally required to sign the bond as well.

Bastardy Bond (1763) (page 1 & 2)

Generally, management of the poor law across the country was inefficient, and high costs of indoor relief had led to Gilbert's Act in 1782,(9) which provided rigid guidelines on how parishes could combine into 'unions'. The Act gave instructions on how to manage a workhouse, and together with a recommended set of rules, the aim was produce standardisation as far as possible. Now, the unemployed able-bodied poor would be provided first with outdoor relief and then with employment, while indoor relief in poorhouses was confined to the care of the old, sick, infirm and their dependant children. In 1776-77, a Parliamentary survey was carried out prior to the Act to ascertain the overall provision of workhouses and poor-relief expenditure in England and Wales. The Abstract of Returns Made by the Overseers of the Poor 1776-7 included an inventory of workhouse provision and lists by county of the parishes or townships operating workhouses and the number of places available in each; Lancaster (extract) The workhouse building in Halewood was not a substantial one, and more likely to be a small two-storey georgian farmhouse, or a cottage similar to those known to exist nearby, such as this example below in Land Ends (where Bailey's Lane meets Church Road). The figure of forty places noted above will be those claiming support, not the number residing within.

The later years of the century saw an economic depression, where, during times of extreme hardship, emergency measures were taken by parishes rather than expect the unlikely scenario of employers raising wages. The Speenhamland system introduced after 1795 was largely applied in the southern agrarian areas, where wages were brought up to subsistence level by the issue of a weekly dole. Farmers took advantage of this and lowered wages paid to their labourers, knowing that parishes would take the burden of the difference. The economic problems this caused over the following decades, attitudes to the pauper, and the demands for a right to a standardised system of relief, pressured the Government into setting up a Royal Commission in 1832 to investigate the Poor Law. When the Commissioners concentrated their inquiry on the extra costs paid out by overseers, the replies from the of parish officials in the West Derby Hundred were either unhelpful or curt. Walton, Much Woolton and West Derby, for example, paid no extra money to able-bodied men in their parishes, Toxteth Park and Everton gave little detail in their replies, while Liverpool, Ormskirk and Prescot were more forthcoming, suggesting that demands increased during the winter and relief was largely unnecessary in the vicinity of an expanding prosperous port like Liverpool. The overall conclusion of the Commission was that most of the poor were aged, infirm or widows. In the rural villages further away from the town, handloom weavers were the only major group who required relief while still in full employment, but they were quite literally a dying breed as the shift towards factory production was expanding.(10)

Following the conclusions of the Commission, the government introduced a Bill which contained most of its recommendations, and while there was great opposition to the proposals from many quarters there was too much disunity for it to be effective. Royal Assent was granted on 14 August 1834(11) and the Poor Law Amendment Act was placed on the Statute Book. The new Act minimised the provision of outdoor relief and made confinement in a workhouse the central element of the new system. To qualify for relief, it was not sufficient for the able-bodied to be poor, they actually had to be destitute. The measure of this was their willingness to enter the workhouse, and it was originally planned that this was to be the only provision for relief. Only the truly deserving - in the opinion of the government - would be those 'desiring' to reside in such a repellent institution. To help them in their decision, the surroundings were made as unpleasant as possible as an obvious deterrent to those seeking relief. Consequently, married couples were separated and children taken from their parents. Overall, inmates were segregated into seven groups according to age and sex; - aged or infirm men or women; able bodied men or women over 16; boys or girls aged 7-15; and children under seven. Each group was assigned its own day rooms, sleeping rooms and exercise yards. They could see each other, but not speak during communal meals or at chapel, and could only meet at infrequent intervals at the discretion of the guardians. By the terms of the Act, a central administrative body was created - the Poor Law Commission, which in turn ordered that parishes were to be grouped together into poor law unions to provide the finance to build the workhouses. Each union was to be run by professional officers under the jurisdiction of an elected Board of Guardians.

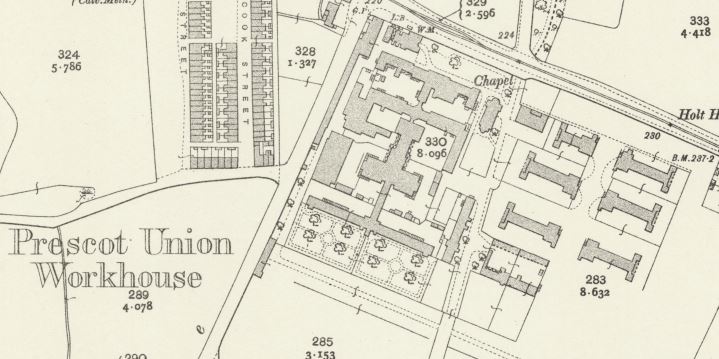

The Guardians immediately declared that the old parish poor houses, now under their jurisdiction, were totally inadequate to cater for the demands of the new legislation. A search was begun to find a site suitable for the erection of a new workhouse, large enough to provide accommodation for the poor of the entire Prescot Union. Initially, the new Prescot Union adopted the existing building at Windle for its main workhouse, with the elderly being placed at the old Sutton workhouse, and children at Much Woolton. Meanwhile, land had been secured in Whiston by the Board of Guardians at the corner of Warrington Road and Dragon Lane, with the sole intention of erecting a new workhouse. The Prescot Union Workhouse opened in 1843, which also resulted in the closure of the workhouses of Bold, Prescot, Much Woolton, Sutton, Windle and Halewood, all inmates being transferred to Whiston. In the nineteenth century, it also housed the mentally ill, but also developed as a Poor Law Infirmary to care for the sick in the days before the National Health Service.

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1840s map

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1840s map

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1906

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1906

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1906 with isolation hospitals

Prescot Union Workhouse - 1906 with isolation hospitals

'…party politics are coming more and more to the one thing - to the idea of social reform - we are getting nearer and nearer every year to the idea that the young and the old who cannot work and cannot keep themselves have a right to be kept by the community…', (11)he was merely outlining the provision of the Old Poor Law, which had been so ruthlessly cast aside over fifty years earlier. The initial care of the destitute fell largely on the shoulders of the parish doctor, who worked for a meagre salary in impossible conditions. They could admit serious cases to the Poor Law hospitals but it was less easy to admit patients to the better equipped voluntary hospitals. Even as late as 1909, the stigma and fear attached to the workhouse infirmary showed no sign of abatement; '...the parish doctor is always available. But the poor do not like the parish doctor and they will adopt any device rather than summon him. They dread what they know to be too often the burden of his message: "You must go into the Workhouse Hospital". Of course, we know it is very silly of them to dread the workhouse hospital but that does not alter the fact that they do dread it, and that they dread the parish doctor...' (12) The respectable poor preferred to endure almost any degree of neglect or misery at home rather than be sent to the workhouse. Dissatisfaction with the Poor Law and disagreement over its objectives again led to the setting up of a Royal Commission in 1905. It concentrated on the relevance of the old Act within a modern urban industrial society, how far charity was funding areas originally covered by the Act, and to what extent new welfare agencies were undermining the provisions of the Poor Law. The Commission found it impossible to find common ground as a united body, issuing conflicting Majority and Minority Reports in 1909. Both were ignored by the Liberal government, but the Local Government Board responded to them by tightening up its administration, especially regarding indoor relief, while Asquith prophesied, 'You will find that Boards of Guardians will die hard'. Meanwhile, 'Lloyd George's Ambulance Wagon,' that vast programme of social reform which might eventually make the Poor Law unnecessary, gained momentum and an opportunity to finally bury the 1834 Act was squandered. Over the next three decades the Poor Law was gradually dismantled. Already in 1908, the Children's Act had given local authorities new powers to keep under privileged children out of the workhouse. On New Year’s Day 1909 old-age pensions were introduced; in the same year labour exchanges were set up to help anyone without work find a job, and in 1911 the National Health Insurance Act was passed which provided state benefit for sickness and maternity. The term 'workhouse' was dropped in 1913 in favour of 'Poor Law Institution' and indoor relief was increasingly confined to the 'helpless poor'; children, old people and the sick. Chamberlain's Local Government Act of 1929 was the death knell for the Poor Law. Unions and their Boards of Guardians were finally swept aside and responsibility for the destitute passed to the new Public Assistance Committees within County and Borough Councils. So began a difficult period of transition in the face of Local Government cuts and stringent economies.

Whiston Hospital

Whiston Hospital

In 1937 facilities were extended to include Out-patients, Casualty, X-Ray, Pathology and an operating-theatre. During World War II provision was also made for military and civilian casualties and prisoners of war. From 1938 it was renamed Whiston County Hospital. In 1948, as a result of the National Health Service Act, the hospital came under the control of the Ministry of Health, but Lancashire County Council retained a section of the old Institution under the terms of the Welfare and National Assistance Act; the section being named Delphside. In 1953, the establishment changed its name again to Whiston Hospital, though the two mental wards were renamed Whiston Mental Hospital. The General and Mental hospitals merged into one in 1959, so that physchiatric patients were just admitted to Whiston Hospital. Since that date there were innumerable extensions and additional facilities added to the General Hospital. In the 2006 the main Hospital was completely demolished (including the Chapel in controversial circumstances) and replaced in 2010 by a modern state of the art building, owned and administered by the St Helens and Knowsley Hospitals NHS Trust.

Extract from the Tithe Map of 1840, and accompanying Apportionment.

The Tithe Map appotionment records that the workhouse plot (no.309) was owned by John Ireland Blackburne, Lord of the Manor of Hale, and newly tenanted by Isaac Lawrenson. The New Poor Law was now operational and there was no longer a legal requirement for a village workhouse.

A decade on, most of the same families were still living in the former workhouse and associated cottages  The workhouse site in 1849

The workhouse site in 1849

Meanwhile, the old workhouse and the cottages were pulled down and the site levelled. On the adjacent plot a new house was erected called 'Wood Lea' shown on the map of 1895 below.  The workhouse site in 1895

The workhouse site in 1895

The workhouse site in 1905

The workhouse site in 1905'Wood Lea' now renamed 'Camelot'.  The 1905 map with a modern day overlay

The 1905 map with a modern day overlay

The workhouse site in 1927

The workhouse site in 1927

'Camelot' now renamed 'Brooklands' and a new cottage built on the old workhouse neighbouring cottage plot site.  The workhouse site in the 1960s

The workhouse site in the 1960s

The 1960s map with a modern day overlay

The 1960s map with a modern day overlay

Crantock Close / Hollies Road

Crantock Close / Hollies Road

The site of the old workhouse and associated cottages Footnotes

1. Act of Parl. 43 Eliz.I, c.2.

Further Reading

Hollinshead, J.E., Halewood Township: A Community in the Early Eighteenth Century' T.H.S.L.C. vol.130. (1981) pp.32-34. Higginbothom, Peter, www.workhouses.org

Archives

The Prescot Poor Law Union was formed in 1837 and in 1843 a new workhouse

was opened on Warrington Road in Whiston. Prescot Union Workhouse later

became Whiston Hospital. The townships of Speke, Little Woolton and Much

Woolton which are now in the City of Liverpool were part of this union.

For contact details for;

Return to Halewood Buildings Page

Visit the Royden History Index Page listing web sites designed and maintained by Mike Royden No pages may be reproduced without permission copyright Mike Royden All rights reserved |