IN THE BEGINNING

When a man is digging his garden in Cheshire in the winter time, and when the land is bare and devoid of vegetation, he may well ask himself about those oddly shaped stones that he sometimes turns up. Where did they come from? By no means all have been left there by the builders of his house and he may well be surprised to learn that at least some will be what scientists call 'erratics' and will have originated in the hills of the Lake District from whence they will have come with the thaw following the last Ice Age.

When a man is digging his garden in Cheshire in the winter time, and when the land is bare and devoid of vegetation, he may well ask himself about those oddly shaped stones that he sometimes turns up. Where did they come from? By no means all have been left there by the builders of his house and he may well be surprised to learn that at least some will be what scientists call 'erratics' and will have originated in the hills of the Lake District from whence they will have come with the thaw following the last Ice Age.

This ice covered the Cheshire Basin from about 60,000 to 10,000 years ago and stretched south into Shropshire where, in places, it has been suggested that it may have been up to 20,000 ft. in thickness. As with all glaciers this carried enormous quantities of debris with it, scrubbed the tops of the sandstone hills and deposited rocks and clay silts in the valleys. A large part of North West England is covered by the Triassic rocks consisting of red sandstones and marls, gypsum and salt. The chief rock in Cheshire is known as the New Red Sandstone.

Farndon lies in the Dee Basin which may be said to extend from the Point of Air to the gorge at Erbistock, and from the base of the Welsh Hills to the 100 ft. contour on the east side of the river. This area is covered in most places with clay soils and silts. The silts being mostly below the 50 ft. contour and close to the river are liable to flooding. The deposits are broken in places by outcrops of sandstone of the Bunter Pebble beds, and the village is situated on one of these sandstone hills overlooking the gorge which has been cut by the River Dee. This sandstone outcrop, perhaps half a mile wide, extends north to Aldford.

In the area of the Peckforton Hills Bunter and Keuper Sandstones can be seen with the latter below. Both are quarried for building purposes, and the Bunter alone is in some places 600 ft. to 700 ft. in thickness. The soil of Cheshire is fertile and the vegetable mould of the drained peat bogs is capable of high cultivation. The thick clay is firm and heavy to plough but productive of rich grass for the farms. Near Farndon, only to the east and south in King's Marsh and Crewe are clay soils which are not very suitable for arable cultivation.

Population

In many fields in the area there are ponds which were dug originally to obtain clay or marl to spread over and enrich the fields. These ponds are called 'pits' (short for marl-pits) and were dug by regular gangs of 'marlers' who went from farm to farm for that purpose. Artificial manures have now destroyed their calling and the pits today are used for watering cattle.

PREHISTORY

When the ice receded the land was first covered by tundra. After this came forests of birch and later of pine trees. As the glaciers melted the sea level rose and the land bridge to the Continent disappeared. The first hunters came to the east coast 9,500 years ago and reached the Pennines some 1,500 years later. Slowly the pines were replaced by temperate forests of such species as hazel, alder, oak, elm and lime. About 5,000 years ago the hunters of former ages were gradually replaced by men who cultivated the land and these began to change the environment. There would seem to be a possibility that Stone Age men who hunted and fished would have been found at times in the Farndon area; there were, after all, oak forests in which they could have lived and probably a plentiful supply of salmon and other fish in the river.

For centuries Farndon has stood on an important crossing of the Dee in that there is relatively high ground on both banks and just above the bridge a shallow crossing which is easily fordable. Although there is no evidence that this was used by early man he would obviously have found some form of crossing extremely important.

The first evidence of human occupation in the area is a Bronze Age burial at Holt just a short distance over the river, an Iron Age fort at Bickerton, and an aerial photograph of a crop mark taken during the dry weather of what would appear to be an Iron Age settlement situated between Farndon and Churton. Ormerod mentions the tumulus at Coddington and several smaller ones at Carden but does not attempt to date them. A late Bronze Age hoard was also found at Broxton.

While there have been no specific finds of this period in the Farndon area it is important to remember that most bronzes have been found in association with the river valleys of North Wales and Northern England. The evidence suggests that the inhabitants lived on the higher ground as found in the hill-top forts of the Iron Age. Farndon is ideally situated for a promontory fort all evidence of which would have been obliterated by the cultivations that have taken place over the centuries. This is only supposition but in any case the population would have been very sparse and have been limited by the food resources. Such people would have lived in primitive timber or mud huts roofed with grass sods and have cooked on stone hearths. Their pottery would have been of such crude nature as to defy recognition by any but expert examination. As there have been no excavations in the village that have been recorded, any evidence of the occupation by such people could easily have passed unrecognised.

Extracted from - Frank A. Latham (Ed.), Farndon: The History of a Cheshire Village, (1981)

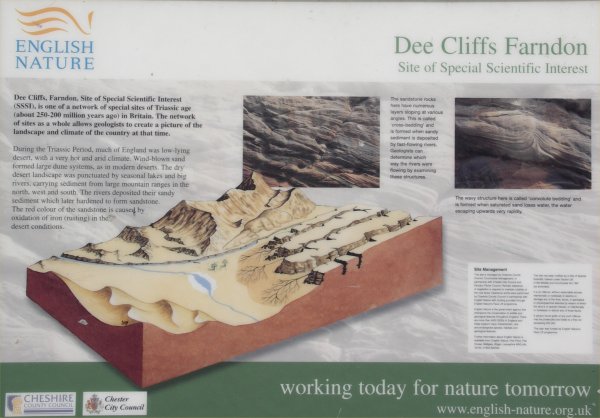

Dee Cliffs on site Information Board

Dee Cliffs on site Information Board